Family History Guide

Articles

Introduction

Hello, if you have just started tracing your family history, then you have already made a great start by coming to Genes Reunited. Created on Guy Fawkes Day 2002, this site was the first British website that set out to connect people like you with other people tracing the same family lines.

What is Genes Reunited?

Before Genes Reunited came along, finding fellow researchers was a hit-and-miss business. In the course of your research, you might well come across a cousin who was also tracing the family tree, and agree to exchange information and join forces. But the problem was finding them in the first place. One of the best ways was using the 'birth briefs' sections of Family History Society journals, in which people listed the surnames they were researching, but of course that depended on seeing the specific edition of the journal in which your long-lost relative had appeared.

The inspiration behind Genes Reunited was to use the Internet to speed up this process of meeting like-minded researchers. It worked, amazingly well. Within months, hundreds of thousands of people were entering the family trees on the site, and finding connections either with actual cousins, or at least with people researching the same surnames, with whom they could collaborate on further research.

Clearly, the site's effectiveness depends on its members – like you. The more people are on the site, the more effective it becomes. As Genes Reunited's membership continues to grow, and as its members continue to add names to their family trees on the site, it becomes ever more effective in its main aim – connecting people, all over the world, who have the same ancestors in common.

How do I start?

The first step is to begin creating your family tree on Genes Reunited. Use the 'Family Tree' tab at the top of the page to start, and fill in the names, dates and other details that you know, starting with yourself. You can then add your parents, your siblings (ie, your brothers and sisters), your partner(s) and children, and so on.

Now, you can start working back, adding details of your parents' parents – your grandparents, and also, if you want, of your parent's siblings and their children (these children are your first-cousins). Then, you can add details of your grandparents' parents (your great grandparents) and of your grandparents' siblings (your great aunts and uncles) and their children, grandchildren and so on (these are your remoter cousins).

Working out the correct terms for your relatives is not as complicated as it may seem at first, and can in fact be rather fun. This relationship chart explains how.

How do I add relatives?

You will find that the system will ask you various questions about yourself, and each relative who you add. The basics are a first and last name, and a year and place of birth for each individual. This is because the site's main aim is to enable people searching for specific relations to be able to find them.

In some cases, you may not know some of the required details, so you have a choice, either put off entering the person until you know more information, or estimate a year of birth (you can tick the 'tick if unsure' box to indicate this) and enter a very rough 'place' (such as 'England'). This is what many people have done, so it is a reminder that, if you don't find someone born in the year you think they should have been born, you should broaden your search to see if they might be found a few years either side.

How can I learn more about my family tree?

As you fill in details of your parents, grandparents and perhaps earlier ancestors, you will find yourself unsure of names, dates and places. At this point, it's time to start asking questions. The details asked when you add details to the site provide you with a neat structure for 'interviewing' your family, asking for names, dates, places, and so on. If you can, start with your own parents – you never know until you ask, what surprises may emerge – you may find, for example, that your mother has a middle name that she has never mentioned before. So, assume nothing, and ask and confirm everything.

You can use the 'notes' section as much or little as you want. Whether your 'interviews' are face-to-face conversation, telephone, letter, e-mail or any other modern method of communication, keep the results in a safe place. If you obtain information through conversations, write down as much as you can, and don't omit the glaringly obvious – the date and time of the conversation and the name of the person who is talking.

Besides names, dates and places, try to build up a profile of each relative, working through their lives. What are their earliest memories? What was their religion, and what role did it play in their lives? What was school like then? Where did they go to school? What options did they have when they left school? If they were involved in wars, as so many older generations were, how were they involved, and how did it affect them? What was their first job? – and so on.

Within each topic, make sure to ask about other members of the family who may have been involved, such as relatives who went to the same school, or followed the same line of work, for example.

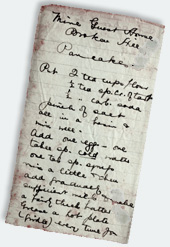

Other interesting questions to ask include whether they have any objects which are family heirlooms – things that have been passed down from earlier generations. Heirlooms may include old family letters, diaries and documents: if so, ask for photocopies or scanned images (the more the better, as making copies automatically increases the chances of such valuable family information surviving for future generations to enjoy). Are there any recipes that they use, that come down from earlier generations? Are there genetically inherited diseases in the family, or any odd genetic traits, such as being able to wiggle your ears, or bend your thumb backwards. Yes – such traits are inherited, and are just as valid and interesting a part of your inheritance as anything else!

Remember – write down and save everything you learn and keep it safe, in a special box or drawer, or if you keep it all on the computer, back-up your information regularly. Get into the habit of noting down the sources of your information – an essential habit that will serve you very well as you start to delve further back in time.

How should I communicate?

Finding out information from relatives is the best way to start your family tree research. Courtesy in letters, e-mails and postings on websites extends beyond the 'please's and 'thankyou's. Make your communications as clear as possible, so that it is easy for the recipient to understand how they can help you. Think about what you want to ask, and what information you want to give, before you start writing. If you write something that you do not feel is completely clear, re-read it, and if necessary re-write it.

Always refer to people by name, rather than by their relationship to you. You know who 'great grandma' was, but from another relative's point of view, 'great grandma' may have been 'aunty', or 'mother'. For a non-relative, it becomes more confusing still. By all means, refer to people like this, but always add their names – not just first names. An e-mail all about 'John' and 'Mary' can be equally confusing. The clearest way to communicate is to write about 'my great grandmother Hilda Wilkins (1898-1966)', 'my father John Evans (b. 1966)', and so on. And, if the same person is referred to again, go to the effort of typing the same details out again, in full, because although you know that you mean the same person who was referred to before, the person reading your communication may not be so sure. Clarity is the most important thing of all in genealogy; a few extra minutes spent writing an email will be minutes very well spent indeed.

How can I extend my family tree further?

Remember to ask each living relative whom you interview for contact details of other relatives. Ask everyone this, from your brothers and sisters to your parents and uncles and aunts and cousins. By doing so, you will start obtaining contact details for ever more distant relatives – second and third cousins, for example – and they in turn may know of other people who are close relatives of theirs, but yet more distant blood-relations of yours.

Your collecting of contact details of ever more distant relatives will be enhanced by Genes Reunited. Perhaps such people may be members of Genes Reunited already. Otherwise, as you enter more names onto your tree on the site, you may find that they match names in other peoples' trees – and discover that those other people are your relatives.

What lines should I trace?

This is absolutely up to you. Most people tend to start with their surname line. Most often, this is the line that goes up through your father to his father, and so on. In cases where parents were unmarried, though, the surname line may go up through a variety of men and women – from your father to his unmarried mother, to her father, to his unmarried mother, and so on. It is a good line to start tracing, because along with genes, objects, cultural traits and whatever else you may have inherited from your different ancestors, your surname is something you share with all those ancestors of yours who bore it before you. Also, it is the name you are most used to – it is surprising how often your will spot your own surname amongst many others – for it is so familiar that it may 'leap' off the page.

However, there are no rules governing which line to start with. Many women prefer investigating the origins of their mother, and their mother's mother, before going up the male line. But perhaps you started your research because of a particular family story about a specific ancestor or ancestral line, or have heard such a story in the course of interviewing your relatives. This may be a tale of great granny Higgses' lost wealth, or of great-great grandpa Gubbins's illegitimate, noble blood. If that is what interests you most, then you should feel free to pursue that line first!

You can research more than line at once. You have, after all, two parents, four grandparents, eight great grandparents, 16 great great grandparents and so on. But that means a lot of families to investigate, and the chance of becoming thoroughly confused is consequently very high! It is usually better to focus on just one or two lines at a time, research them properly, and then move on to look at the others later. All the time, keep updating and correcting your tree on Genes Reunited, so that other, new researchers out there will be able to find you.

Is the information I have been told accurate?

Most information you are told by relatives will be broadly true, but contain some inaccuracies. The same, inevitably, goes for some of the information you will find entered by other people on Genes Reunited. Occasionally, along with the odd small mistake, you may encounter information that is wrong. You should maintain a degree of healthy skepticism at all times and don't be surprised (or disappointed) when you find your ancestors were real people.

Sometimes, people simply lied. Most often, this was for an innocent reason – to cover up an illegitimacy, for example. Equally, sometimes people make mistakes when researching their family trees, and trace the wrong lines. Someone here on Genes Reunited may have entered a 20 generation family tree to which you can connect, but the earliest 15 generations might be completely wrong.

Always, the way to spot and correct all such blunders is to do a little research of your own in the original records. Look for unlikely connections – a Yorkshire aristocrat may have been the father of a Cornish tin miner, but you can always ask (politely) to see the evidence, and if you're not convinced, see if you can research a more plausible father for the Cornishman. Remember, family history is a life-long game of detection and research, and the more work you do, the more accurately you will come to understand who your ancestors really were, and the nature of the world that they inhabited.

How do I expand my research using records?

As you work back, you will reach generations about whom your relatives will not be so certain. They may know great grandpa's name, but not exactly when or where he was born. You may be told who your great great grandmother was, but nobody will remember what her own mother was called. It is at this point that you should start using original records. If your family are from England and Wales, you can use the census returns and General Registration records of birth, marriage and death (sometimes referred to as 'BMD' records), available in the 'Search Records' section of Genes Reunited.

If your ancestors were not from England and Wales, then you will need the equivalent records for the country where your family lived. Many of those that you will need for Scotland are on a single website, www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk. There is no such unified website for Ireland, and indeed the majority of Irish records are not yet on-line. How to undertake research in Ireland is explained in Anthony Adolph's book Tracing Your Irish Family History (Collins, 2007).

Any questions?

Genes Reunited has an active set of message boards for you to post your queries and maybe help other people who are stuck. Once a month, our resident genealogist Anthony Adolph holds an hour-long live question-and-answer session at Ask an Expert where you may have your question answered, or pick up tips from his answers to questions similar to your own.